Imagine a presidential candidate with the pedigree of John F. Kennedy, Jr. and the track record of William Jennings Bryan. Like JFKJr, Cuauhtemoc Cardenas Solorzano is the son of a beloved 20thcentury president (Lazaro Cardenas (who nationalized the oil companies). Like WJB, Cuauhtemoc Cardenas ran for the presidency three times (under the banners of a coalition of populist, reform, and leftist parties) only to lose three times.

Young Cardenas rose rapidly in the ranks of the PRI and served as governor of the western agricultural state of Michoacan in the 1970s (where he was best remembered for the abolition of prostitution). He made known his aspirations for the presidency, but was told that it was Miguel de la Madrid's turn in1982, so he patiently waited another six years. When de la Madrid then gave the finger of nomination (el dedazo) to his finance minister,Carlos Salinas Gortari, Cardenas refused to sit by quietly, but decided to run as a third party candidate.

Since that time Cardenas has been a major polarizing figure in Mexican politics. No one is neutral about CCS: either you love him or hate him. His admirers view his 1988 (and subsequent) campaigns as a selfless quest to reform the country, while his detractors have seen him as a tireless self-promoter who can't seem to take three "no's" for an answer.

In the 1988 election, Cardenas started with his own new party, PFCRN (Partido Frente Cardenista para laReconstruccion Nacional). He then worked a political miracle unifying the scattered parties of Mexico's left: PPS (Partido Popular Socialista), PSUM (Partido Socialista Unida de Mexico), and PARM (Partido Autenticade la Revolucion Mexicana). Only the old Trotskyites of Partido del Trabajo resisted his call (at that time).

To understand Mexico in 1988, you have to understand that it was still in a throes of an economic crisis,and the PRI candidate, Salinas Gortari, was seen as the architect of the economic policies which had been painful (and had not yet born fruit). The conservative PAN (National Action Party) had won some governorships in the north and had nominated a respected agribusinessman from Sinaloa, Manuel Clouthier.

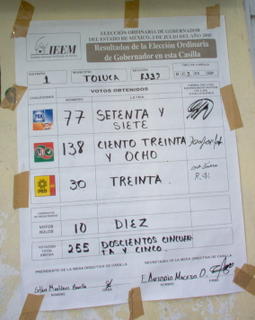

Every Mexican I have ever spoken with since July of 1988 was convinced that Cardenas won (although I did read one article which speculated that maybe the real popular vote victor was Clouthier!). In any event, no one thought that Salinas got more than ten percent of the real vote, but after more than a week of falsifying the totals, the PRI-dominated electoral commission declared that Salinas had won the three way race with 50.1%.

To his credit, Cardenas did not call for a revolt. He decided to pull his supporters into a new party, PRD PartidoRevolucionario Democratico. Some local chapters, like the one in Acapulco, attracted broad support from academics, business, labor, and old PRI reformers, and started to win seats in the congress and mayorships.

In 1994 Cardenas was ready to try again, but initially this appeared inappropriate, for the PRI had chosen a youthful reformer, Donaldo Colosio. Also, the economy was on an upswing: it looked as though Salinas' bad tasting medicine had worked. Then, Colosio was assassinated and thePRI went for a replacement candidate completely out of character, the introverted but competent Ernesto Zedillo.To everyone's surprise, he agree to debate Cardenas andthe PAN candidate, Diego Ceballos. Not accustomed to formal debates, Cardenas performed poorly. Ceballos shined in the first, focusing his brash attacks onCardenas. In the next debate Zedillo's soft spoken confidence lifted him about the rhetorical duel of the other two. On election day,Cardenas came in a distant third. Despite some local frauds, I think that the positions of the candidates would not be changed by a more thorough and honest count.

In 1997 Cardenas decided to run for governor of DF, the federal district (equivalent the mayor of Mexico City). Since he had carried DF in both of the presidential elections,it was a safe bet. For the next three years, he used that office as a platform to posture, and blame the PRI for

not letting him succeed.

The 2000 presidential race had new candidates for the PRI (Labastida) and PAN (Coca Cola president turned Guanajuato governor, Vicente Fox). The presidential debates had a pattern similar to those of six years before. Tracking polls revealed that Cardenas started off in last place, and lost ground as the campaign went on. Voters who wanted real change, left Cardenas and headed for the rising Fox. Voters who wanted to prevent a PAN victory, left Cardenas and voted for Labastida.

Over the last few years, another PRDista with presidential aspirations has followed Cardenas' path, moving from Tabasco to Mexico City to occupy that springboard position. Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador AMLO now seems the favorite to win not onlythe PRD nomination, but the presidency. Last March, when it appeared that AMLO would be disqualified from running (on some rather questionable charges), Cardenas let it be known that he could be persuaded to run a fourth time. That idea sold as enthusiastically as a three day old fish in Acapulco's municipal market. Now it appears that AMLO will not be disqualified, so Cardenas has decided to make the retirement announcement.

Cardenas says that he will now devote his time to building a great coalition to work on progressive causes: "Un Mexico Para Todos." He got off a few parting shots, criticizing his party for its structural weakness,absense of debate about priorities,recent ideological detours and the propensity to seek alliances (most recently with Partido del Trabajo). I'm sure his admirers will continue to see him as the guiding beacon of the left, while his detractors will read into his latest words a mixture of bitterness and self-justification.

Leaving the stage, we have the most colorful figure inMexican politics since ... his father.